Werner Herzog and Roger Ebert at Ebertfest, 2007. Photo by Jim Emerson

Roger Ebert's last review is on the screen in front of me and I can't quite bring myself to deal with it. I'd like to get it posted right away because I know that's what Roger would want under the circumstances. ("We'll be getting a lot of traffic!") Actually, he filed two or three other reviews before his condition took a sudden turn for the worse. But this final one -- sent March 16 and labeled "FOR USE as needed," is of Terence Malick's "To the Wonder," which (spoiler warning) he liked quite a lot. Publicists might object that it hasn't opened in Chicago yet, but Roger wasn't just a Chicago movie critic (though he certainly was that). I can imagine his email now: "Who's going to complain? It's three and a half stars!"

In his 46 years as film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger wrote more than his share of obits and posthumous appreciations on deadline -- hardly ever in advance, like the ones most newspapers have on file, ready to publish at a moment's notice, but off the top of his head on the day the news broke. For years, I did that for other papers and web sites, too. But this isn't just another obit; it's one of the hardest things I've ever had to write. Still, I know he'd want me to do it -- and to get it online ASAP so he could, as he said, "socialize" it -- tweet it and Facebook it.

I honestly expected Roger to outlive me. As Pablo Villaca, one of Roger's "Far-Flung Correspondents" (or FFCs as they are affectionately known), wrote this afternoon: "We are orphans now." And that's the way it feels. (Oddly, my own father died six years ago on this very day -- which Roger would acknowledge is a kind of apt coincidence, though not anything of "woo-woo" supernatural significance.) But I want to avoid anything maudlin or sentimental because he hated, hated HATED that sort of thing.

The bond between a writer and an editor can be a surprisingly intimate one, and for almost 10 years Roger and I ran RogerEbert.com as basically a two-man operation. His Chicago Sun-Times editor for 20-plus years, Laura Emerick, edited all of Roger's writing that appeared in the paper, and we always tried to use her expertly edited versions online, but sometimes he'd write other stuff exclusively for the site, or that would appear on the web first, and I would edit those myself. At first our site also had the support of the Sun-Times, including Catherine Lanucha, John Cary, Jack Barry and the company's webstaff, but budget cuts and layoffs at the paper eventually left us with no day-to-day resources but ourselves: the only two employees of RogerEbert.com, as we liked to joke. But it was true. (BTW, nobody edited Roger's blog; it was direct from him to you, which is what a blog should be.)

Mostly, I maintained the site, reading, formatting and publishing reviews and articles new and old -- forever correcting typos, import errors and formatting glitches in the thousands of reviews in the database that went back to when Roger started reviewing for the Sun-Times in 1967.

Above all, I read and responded to emails from Roger -- thousands and thousands of emails (all archived, because I would often need to reach back years to remind him of how and why we'd made certain decisions, or to clarify matters). They ran the gamut of subjects and varieties -- questions, ideas, notifications, requests, bug reports, jokes, philosophical musings. It wasn't unusual to get 10 or 20 in a 14-hour stretch. And they were sent, and replied to, at all hours of the day and night, 365 days a year -- Roger using his MacBook in Chicago (or Cannes or Toronto or Telluride or Park City or Mexico or Los Angeles or Pritikin or wherever he happened to be) and me working mostly from home in Seattle.

As his output amply demonstrated, Roger wasn't just a recovering alcoholic (one of his favorite topics, along with Darwinian evolution), but a workaholic. He would invariably insist on writing something that just had to be posted on July 4 or Christmas Day (even though it had nothing to do with American independence or Christmas and could just as well have waited). He was oblivious to the concept of weekends, holidays or any limitations on working hours. He really liked to write. But, if you read him, you know that. (One Oscar night I got mad at him because Laura and I were waiting for the final version of his Oscar story and I discovered he was tweeting about other things while we were on a tight deadline. That's when I found out he was using a Twitter-scheduling app, so he could load up his tweets in advance and it would post them automatically. Yes, he practically worked round the clock, anyway -- but even when he wasn't working, he got software to do the tweeting for him.)

Now, I hate those "In Memoriam" pieces in which the writers overstate their closeness to the deceased. I started working with Roger in 1994, when I was the editor of Microsoft Cinemania, then became his web editor when we founded RogerEbert.com in 2003, and have remained so ever since -- the longest time I've ever held a single job, although the job kept changing and I stayed put.

I'm not so presumptuous as to say I knew All About Roger -- but I knew certain aspects of the guy probably as well as anybody, particularly when it came to his thoughts and feelings about various things that were dear to him, like the newspaper business, movie criticism and various ethical and philosophical issues. You don't read and correspond with somebody (particularly a writer) every day for 10 years without learning something about their tastes and sensibilities, their use of language, the principles they believe in, and how they prefer to conduct themselves in the world. But he had many, many different sides to him -- some of which he shared, some he didn't. I often learned personal details, particularly about his health, when he'd write something on his blog months or years after the fact.

I'm most grateful for Roger's friendship, trust, and generosity. As much as he lived his life in public, he was also intensely private. But he loved to gather people around him. In 1997 he extended the invitation for me to join the Floating Film Festival as one of its critic/programmers. It was helmed by Dusty and Joan Cohl, who quickly became two of my favorite people. He introduced me to the Conference on World Affairs in Boulder, CO, where he conducted the week-long Cinema Interruptus (now the Ebert Cinema Interruptus) program for more than 30 years and asked me to join him in the process. A few years later, after he lost his ability to talk, I was able to step in and continue the tradition he had started.

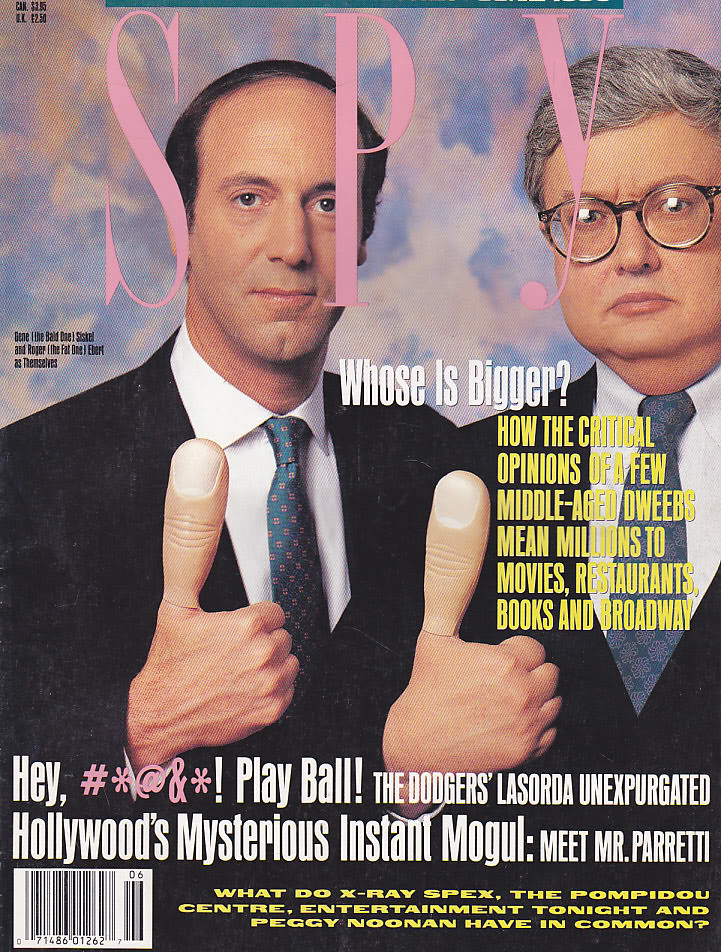

And, of course, there was Ebertfest, where I instantly bonded with film scholars David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson, now good pals, and befriended Roger's Far-Flung Correspondents (the formation of which was an urgent inspiration he had one Thanksgiving weekend when I was in Oregon trying to have dinner with friends) and The Demanders.

For Roger, the ideal life was a moveable party, with him as the host, seated at a big table with a circle of friends and colorful characters. That's basically what Ebertfest was, but I sat at that table many other times in many other places, from the Red Lion, a lodge in the hills above Boulder, to ships cruising the Caribbean or the Panama Canal during the FFF. As much as he would sometimes complain about being a "celebrity," or being noticed because of "that damn TV show," nobody thrived in the spotlight more than Roger (with the possible exception of Quentin Tarantino).

I'm tempted to say that if Roger had never written a word, he'd be known for bringing people together. But the writing was what made Roger Roger. He wasn't just generous with those close to him. He told everyone a lot about himself -- sometimes, I think, more than he knew -- in the words he published: his reviews, his op-ed pieces, his interviews, his blog, his memoir -- even his tweets.

At this moment, I know that thousands of others all over the world are collecting their thoughts and memories of Roger. I often felt awkward and out of place, like I was just in the way, when I tagged along with him in public and he was surrounded by fans, well-wishers and gawkers -- and I feel that way now. I'm overwhelmed -- with affection, gratitude, regret, sadness. So I'm getting back to work.

In one of Roger's last emails, responding to my concerns that he was firing off messages that were garbled or didn't make sense, he said he sometimes felt that way himself, but wanted to assure me that he was still in possesion of all his marbles.

"JIm, old friend, I'm in bad shape. I type on my lap in a hospital bed. I'm on pain meds. Did the review of 'To the Wonder" make sense e to you? Such a strange movie.

"I need your help."

You've got it, R.

- - - - -

P.S. Last night, when I was publishing the new reviews for the week as usual (I haven't had a Wednesday off in years!), I wrote a headline for my review of "Room 237": "A whole world lies waiting behind door No. 237." I was going to call it to R's attention because he'd recognize the reference. It's from a song written by Jimmy Buffett and Steve Goodman, and Roger was a big fan of the latter. I think it would have made him smile.

Funk and Seamon rightly conclude this portion of

Funk and Seamon rightly conclude this portion of

While the rule under the amended law is

While the rule under the amended law is It was

It was And then there's slow-burning,

And then there's slow-burning, Last weekend, Reason

Last weekend, Reason On Wednesday in Denver, the

On Wednesday in Denver, the The current issue of Science has an

The current issue of Science has an

Having

Having  The

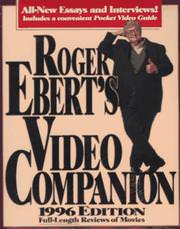

The But if the TV show ensured that Roger Ebert was

But if the TV show ensured that Roger Ebert was And that

And that FoxNews.com reporter Jana Winter is

FoxNews.com reporter Jana Winter is  President Obama, just a few

President Obama, just a few Yesterday I

Yesterday I